Nurse Anesthesia Diversion Prevention

A Knowledge and Needs Gap Analysis

Joshua Ades, DNP, CRNA , Christopher Sims, DNP, CRNA, Shea Polancich, PhD, RN, and Stephanie Hammond, DNP, CRNP, ANP-BC, COHN-S

Abstract: Background: Substance misuse is an occupational health problem for anesthesia providers (APs). More than 10% of nurse anesthetists misuse and divert medications. No standard exists for addressing AP drug diversion. The purpose of this quality improvement project was to evaluate the use of a knowledge and needs assessment to inform the development of a successful drug diversion prevention program for certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) and student registered nurse anesthetists (SRNAs). Methods: A 28-item questionnaire, using the health belief model (HBM) and the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework, was developed to assess knowledge, beliefs, and practices of substance misuse and diversion. RPA groups were determined by level of belief in self-risk and perceived efficacy of prevention strategies. The survey was emailed to 100 CRNAs and over 100 SRNAs. Survey results were organized using the RPA framework. Findings: One hundred twelve surveys were completed. The RPA avoidant category (high-risk belief and low perceived efficacy of preventive interventions) comprised 52.5% of CRNAs; SRNAs were divided primarily among the RPA responsive category with high perceived risk and high-efficacy beliefs (38.9%) and the indifferent category of low-risk beliefs and low perceived efficacy (31.9%). Conclusions/Applications to Practice: Anesthesia providers have varying beliefs regarding drug misuse and diversion risks and perceptions of their ability to be successful with preventive strategies. Failure to address nurse anesthesia needs-based diversion prevention may result in missed opportunities to educate this group. Implementation of RPA-tailored interventions by health care organizations may produce effective, long-term outcomes for drug diversion within the profession.

Keywords: drug diversion, nurse anesthetist, substance abuse, anesthesia provider

Background

Substance misuse is a growing public health problem in the United States (Sederer, 2015). The National Institute on Drug Abuse (2018) reports that human casualties over the last 20 years from overdose have more than quadrupled, and the overwhelming majority of these deaths occurred from opioid misuse. Healthcare providers are at risk for substance misuse primarily related to accessibility to opioids and other addictive medications used in medical practice (Epstein et al., 2007). Certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) have become the largest group of anesthesia providers (APs) in the United States. Substance misuse in this population remains an occupational hazard (DeFord et al., 2019). Bell et al. (1999) were able to document more than 10% of CRNAs misuse and divert medications. Regrettably, Bell’s work has not been replicated in recent years.

Substance misuse among CRNAs results in severe consequences to both providers and patients alike (DeFord et al., 2019). In the operating room, the morbidity and mortality from drug diversion is an occupational hazard. This hazard needs to be addressed (Epstein et al., 2007). More measures need to be identified and implemented to prevent the increasing prevalence of substance misuse among APs (DeFord et al., 2019).

Diversion is defined as unlawful distribution or use of a substance after the transfer from its legal and original use or intended purpose (Berge et al., 2012). Drug diversion may affect everyone involved; the diverting and misusing provider, patients under the provider’s care, colleagues, staff, and employers (Berge et al., 2012). Diversion is difficult to identify and many times is not reported. According to Lien (2012), over one-third of healthcare providers who are aware of an impaired colleague do not report the colleague. Individuals who do not report often feel that the issue will be managed by others or that the information will be ignored, while some

Applications to Professional Practice

Medication diversion and substance misuse is a leading occupational health concern. For APs, this is the leading health issue. Diversion often goes unnoticed, but when it is noticed, it is often under-reported. While safety checks and balances have been enhanced, so have medication diversion tactics. The purpose of this project was to develop awareness to the issue, educate providers of the importance of this occupational health issue, implement new protocols and policies, and develop new methods to fight this epidemic plaguing the health care systems and this country.

Preventive interventions can work; however, education prevention interventions must be tailored to the needs of the AP. Needs can be accessed and grouped based on RPA model. These groupings can guide the development of tailored interventions.

Healthcare facilities might consider an evidence-based strategy to address substance misuse and drug diversion. The strategy can include RPA-tailored prevention education to improve efficacy beliefs with communication. Other strategies include improved technology and the use of automated drug dispensing cabinets, support for those who do report suspicion or knowledge of substance misuse, random drug screening, support for the person who is diverting medications, and facility-specific policies and procedures.

are fearful of punishment or retaliation if they report a peer or colleague (Lien, 2012).

Patients may be unaware of the growing concern associated with provider substance misuse until a drug diversion event occurs (Bryson & Silverstein, 2008). This brings concern for many, and is multifaceted, as patients rely on APs to take care of them, protect them, and advocate for them while under their care. Compromised care, failure to administer needed medications, transmission of viral and bacterial organisms, and deaths have all been attributed to or caused by diversion of medications by health care workers (Pelt et al., 2019).

According to Bryson and Silverstein (2008), safety systems have been created to improve patient safety and discourage drug diversion, but are either not being used correctly, or not being used at all. The use of dispensing machines for medications and newer information technology systems provides better detection of drug diversion within the health care environment. The screening of individuals working in health care settings with reports of suspicious medication withdrawal also helps (Epstein et al., 2007).

Substance misuse is a major health concern for APs (Tetzlaff et al., 2010). Anesthesia providers (anesthesiologists, CRNAs, anesthesia assistants, anesthesia residents, and student registered nurse anesthetists [SRNAs]) use highly addictive medications each day and can easily divert or misuse these medications. This is an emerging occupational health issue for APs. Due to the lack of literature addressing this topic, researchers are unable to establish the extent of substance misuse and diversion among APs.

The purpose of this project was to implement and evaluate data obtained from a knowledge and needs assessment that would serve to assist in developing specific interventions to address the gaps in knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs related to substance misuse and diversion among the profession and encourage reporting of drug diversion.

Methods

A literature review on current practices for drug diversion prevention and detection in APs was conducted using CINAHL, the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PubMed as search engines. Search terms used were: “nurse anesthetist,” “anesthesia provider,” “anesthesiologist,” “substance abuse,” and “drug diversion.” Fifty-three articles were identified in the search. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to reduce the number of articles. The inclusion criteria included: full-text articles, peer-reviewed articles, articles written in English, articles written within the last 8 years, and articles involving only APs and healthcare settings. The authors then reviewed the articles by title and abstract; articles were selected based on relevance to prevention and detection of AP substance misuse and drug diversion. Due to limited results from the inclusion criteria, the search was extended to include articles within 20 years. Sixteen relevant articles represented the final yield.

The 16 articles yielded three key themes: (a) drug delivery systems that were not sophisticated enough to catch diversion; (b) variations in education, prevention, and detection; and (c) lack of diversion and substance misuse reporting. In summary, this literature review highlighted several shortcomings leading to increased incidence of drug diversion in this population.

Two theoretical frameworks were used to support this project: the health belief model (HBM), and the risk perception attitude (RPA) model. The HBM explains that one’s behavior depends on their perception of how severe the illness and how susceptible the individual is to the illness; benefits of steps to prevent the illness; and barriers to taking steps to prevent the illness (Nursing Theories, 2012). Action cues are an integral component of the model. Applied to the substance abuse challenge in APs, the HBM supports the belief that if (a) substance misuse is a serious health problem, (b) one is perceived as being ethically responsible for a patient’s safety, and (c) if the benefits of drug diversion reporting are greater than the risk of punishment, one is more likely to take ownership of actions. These behaviors would include the act of self-reporting or disclosing the concern of diversion by a peer. The difference in the two frameworks is that the HBM, the older model, did not initially include efficacy and postulated that if people perceived risk, they would change their behavior.

The RPA was selected as the conceptual model to support the identification of knowledge leading to the improvement of provider wellness. The model elements include that if people perceive risk and they believe they can change behavior, then they will do so. A modified version of the RPA framework was used for this project, adapted to include Rimal’s (2001) study of individual risk and self-efficacy. For this project, integrated perceived AP risk along with individual efficacy beliefs of institutional interventions was measured. According to Rimal (2001), perceived self-risk has been linked to increased awareness of individual vulnerability to certain diseases or harmful behaviors, and as individuals’ perceived risk increases, they are more motivated to act in self-protective behaviors or seek information to decrease their risk. In a later study, Rimal and Real (2003) divide individuals into one of four distinct categories of responsive, avoidant, proactive, and indifferent. Groups are determined by their level of belief in self-risk and perceived efficacy of prevention strategies.

The responsive group is defined as those individuals who have elevated levels of perceived risk and a high belief in the efficacy of institutional prevention tactics. This group has an increased awareness concerning their risk potential and believes that they have available knowledge and tools to prevent said risk. The avoidant group typically exhibits high-risk beliefs and low-efficacy views. This group has a similarly high-risk belief; however, the avoidant group has a decreased awareness of safety interventions and behaviors. Low-risk assumptions and high-efficacy beliefs define individuals who fall into the proactive group. This set of individuals do not perceive themselves at risk but have a strong desire to adapt to injury prevention behaviors. Finally, the indifferent group tends to display low-risk beliefs and low perceived efficacy of preventive behaviors. The indifferent group is low-risk and low perceived efficacy. This population does not think that risk is a factor, nor do they believe in preventive measures to divert individual harm.

Survey Development

Using guidelines developed by Upton and Upton (2006), a survey was developed to assess the knowledge gaps and needs for APs to identify methods to address substance misuse and diversion. This survey is available online as a supplement.

A 28-question Likert-type scale online survey was developed and distributed via email to 217 SRNAs and CRNAs from a third-party survey development company, Qualtrics®. Survey participants included SRNAs enrolled in the CRNA program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and CRNAs currently practicing at a large urban hospital.

Included in the email was the link to the survey along with a letter describing the project and its intentions. Participants were ensured confidentiality, and 113 surveys were completed (52.1 % total response rate). The survey was distributed twice over a 2-week window via email.

Researchers requested that the SRNA program director at the School of Nursing and the director of perioperative anesthesia services at a large urban hospital distribute the survey via email to their participating cohorts. The email described the study and provided a secure link to the Qualtrics survey. Survey completion provided participant informed consent. The survey required less than 10 minutes to complete.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the survey responses. At the close of the 2-week survey deployment and response period, the survey data from Qualtrics were exported into an Excel™ spread sheet. Data security was insured by limited personal and password access. Risk and efficacy scores were evaluated for the variables of age, gender, role, and education. Cross-tabulation analysis was used to evaluate risk and efficacy categories using two variables, which measured either provider risk perception or efficacy beliefs of institutional interventions. Data analysis was performed using SPSS for MAC version 26™. Descriptive statistics included frequencies, percentages, and means which were used to evaluate survey variables as applicable to the level of measurement. Each Likerttype question was scored from 1 = strongly disagree to 4= strongly agree based on the chosen answer. There were seven risk questions and nine efficacy questions. A score of 21 or greater on the risk questions indicated that the participant had a high-risk belief. Likewise, the perceived efficacy questions with scores of greater than 27 separated participants into a highefficacy belief. After determination of risk and efficacy beliefs, participants were placed in groups based on RPA definitions. The remaining questions in the survey were related to age, gender, years of experience, and education. The project was approved by the ethics committee at the School of Nursing as a Quality Improvement (QI) project, not requiring Institutional Review Board (IRB) review.

Results

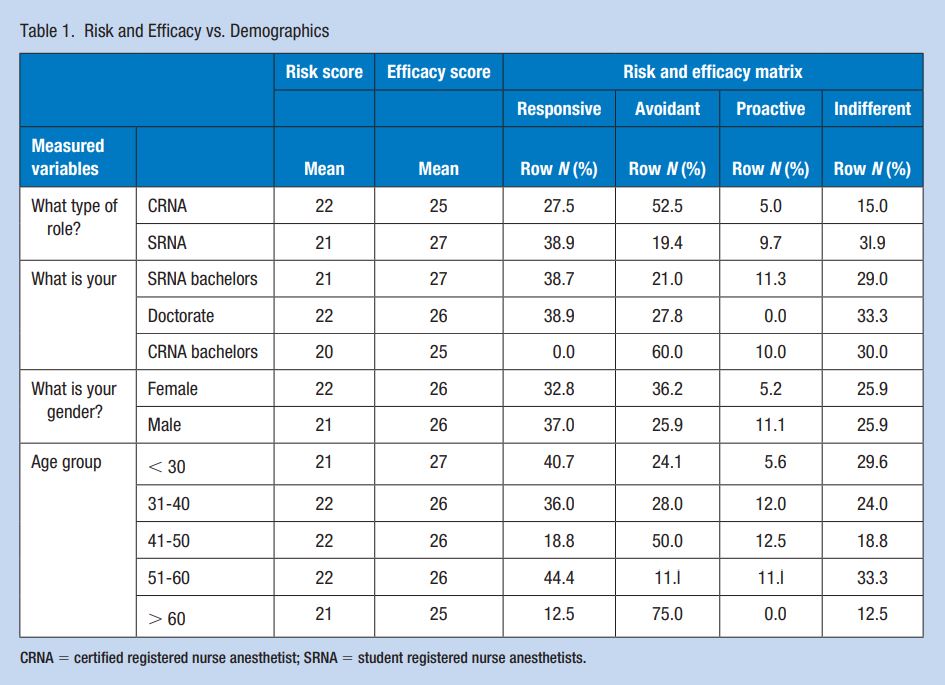

More than half (52.1% response rate) of the surveys sent out were completed and returned (113 surveys were completed). The sample size included 74 SRNAs and 37 CRNAs. A review of the demographics (Table 1) revealed that 48.2% of the respondents identified as male and 51.8% identified as females. Age distribution was: 48% were less than 30 years old, 22.3%, 31 to 40 years old; 14.3%, 41 to 50 years old; 8.0%, 51 to 60; and 7.1%, greater than 60 years of age. Years of nursing experience for the SRNAs subgroup indicated that 60.8% had less than 5 years, and 37.8% had 5 to 10 years of nursing experience. Reported CRNA years of experience included: 10.8% with less than 5 years, 13.5% with 5 to 10 years of practice, and 27% with 11 to 15 years. The remaining 48.6% of the participants had greater than 16 years of practice as a CRNA. Participants’ level of education was evaluated to include: 64% of the participants held bachelor’s degrees; 55.4% of SRNAs and 8.9% of CRNAs 8.9% had bachelor’s degrees. Master’s-prepared respondents represented 19.6% and doctoral degrees 16.1%. The percentage of doctoral-prepared participants also included a segment of SRNAs who recently graduated but had not taken the nurse anesthesia certification exam. Risk perception and institutional prevention efficacy were explored in relation to gender, education, and role using descriptive statistics and crosstabulation comparisons.

Risk Efficacy Results

Regarding risk and efficacy beliefs, more than half (52.5%) of the respondents with the role of CRNA (n = 37) scored in the avoidant category and 11 (27.5%) were noted as in the responsive group. With respect to the SRNA role (n = 74), respondents were spread mostly among the responsive group (n = 28 or 38.9%) and the indifferent category (n = 23 or 31.9%). The remaining 19.4% for SRNAs were categorized as proactive and avoidant represented 9.7%. Among the respondents, females answered with greatest numbers as either avoidant (n = 21or 36.2%) or responsive 19 (32.8%). Males reported as responsive (n = 20 or 37.0%) with a quarter (25.9%) demonstrating avoidant characteristics. Similar to role results a visible difference in RPA grouping was noticed with age. More than a one-third (39.2%) of the 79 respondents less than 40 years old indicated responsive RPA beliefs. In contrast, of the 33 individuals greater than 40 years old, nearly, half (45.5%) represented avoidant RPA responses. The majority of SRNA respondents were in the less than 40-year-old groups. In terms of education, each level of postsecondary education was represented which included bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoralprepared individuals. However, bachelor and doctoral-prepared respondents were represented in both SRNA and CRNA roles while all the master’s-prepared were only CRNAs. With respect to education, 38.7% of those with bachelor’s degrees represented responsive RPA beliefs, while 50% of those with master’s degrees reported avoidant RPA characteristics. In contrast to SRNAs holding bachelor’s degrees, 60% of CRNAs with a bachelor’s degree held avoidant beliefs. Furthermore, most doctoral-prepared responses were split between responsive (38.9%), indifferent (33.3%), and avoidant (27.8%).

Anesthesia provider diversion risk perception was consistently scored as high across role, gender, age, and education. However, the group scoring highest in the efficacy category was SRNAs less than 40-year old. These subgroups demonstrated more responsive RPA characteristics when compared to other subgroups.

Discussion

Levels of Risk Perception and Efficacy Beliefs

The levels of perception related to risk for drug misuse and diversion and efficacy beliefs related to institutional intervention success were measured independently among respondents before the final categorization into RPA groups. The predetermined question scores of how respondents perceived CRNA risk and efficacy beliefs of the facilities’ prevention interventions were used to determine whether a category of participants had characteristics of high or low provider risk perception and diversion prevention efficacy beliefs. Mean scores were calculated for the variables of age, role, gender, and education. These scores were used to differentiate high vs. low risk and high vs. low efficacy.

The results of this survey demonstrated variations in knowledge and beliefs in relation to AP risk and drug diversion prevention practices. Patterns were found that had differences in risk perception and efficacy beliefs based on the variables. Previous researchers demonstrated that risk and efficacy beliefs affect overall work safety behaviors (Real, 2008). Evidence has previously shown that proactive and responsive workers were more likely to engage in preventive safety practices (Real, 2008).

This survey suggested that CRNAs were more likely to demonstrate avoidant behaviors in which they saw themselves in high-risk positions, but their belief in the efficacy of prevention measures was low. This potentially indicated that as institutions’ diversion prevention initiatives are improved so will beliefs in diversion prevention policy and interventions among CRNAs. In contrast SRNAs as a group primarily demonstrated responsive and indifferent characteristics. While a responsive RPA characteristic is a positive trait in high injury risk environments, the opposite may be said for indifferent RPA beliefs. Bozimowski et al. (2014) reported that the likelihood of drug diversion is often seen in CRNAs less than 30 years of age postgraduation. The low risk and efficacy beliefs, as defined by an indifferent RPA may explain this phenomenon.

Responsive vs. Avoidant RPA

Paek (2014) explains that the perceived risk for harm is an individual’s perception that the likelihood of self-harm or injury may occur. The level of perceived risk is vital to an individual’s behaviors to mitigate these risks (Paek, 2014). Previous researchers have hypothesized that diversion risk is related to several factors, including ease of access, occupational stress, and psychological desensitization (Samuelson & Bryson, 2017). Despite these and possible other factors, this study suggests that CRNAs and SRNAs understand and recognize the risk of diversion associated with the profession. The sample group as well as subgroups (role, age, sex, and education) consistently scored high in terms of perceived diversion risk. This consistent trend resulted in a decreased number of participants or subgroups within the indifferent (low risk, low efficacy) and proactive (low-risk and high-efficacy) RPA groups. Continuous and repetitive open acknowledgment of provider risk by providers and healthcare institutions is the first step in preventive strategies. Data are clear that providers understand this risk; however, more evidence is needed to ascertain if healthcare facilities understand this unique risk.

The survey suggested that differences in the perceived efficacy of diversion prevention efforts by CRNAs and SRNAs were most likely. For example, the data suggested that CRNAs score low on the efficacy belief scale resulting in an RPA avoidant group (high-risk, low-efficacy belief). In contrast, SRNAs were represented by responsive (high-risk, high-efficacy) qualities. These results indicated the importance of tailoring diversion prevention education, interventions, and campaigns in relation to the efficacy beliefs of providers. Real (2008) states that if individuals felt that an organization openly made relevant safety information available, individuals will seek opportunities to initiate safety behaviors. Practitioners with higher efficacy beliefs tended to have a greater level of safety awareness in terms of positive safety behaviors and the seeking of safety information. Likewise, if safety information was not presented in a manner that was conducive and specific to an individual’s risk/efficacy profile, the potential effectiveness may be diminished (Real, 2008). The communication and education of diversion prevention directed toward CRNAs and SRNAs would therefore require specific techniques. Moreover, differences within each subgroup further support the idea that multiple education techniques are warranted.

A primary limitation of this study was the lack of recent literature from which to draw theoretical support. Other limitations with this QI project include: lack of current data, sample size, time, and timing. The survey was developed with our clinical partner, UAB, to survey the practicing CRNAs and SNRAs at UAB. Participation was voluntary. The lack of current data to design the survey tool required altering the inclusion criteria to include earlier articles. These articles, some over 25-year old, may not accurately capture the growth of or issues with diversion today. There was limited time to complete and return the survey at a time when the pandemic was starting. The impact COVID-19 had on participation in the survey is unknown.

Implications for Occupational Health Practice

Anesthesia providers, in general, understand the diversion and misuse risk associated with their occupation. However, little is understood about how to address this risk and few are familiar with interventions that could help them. These findings have strong implications for health care facilities and anesthesia programs that wish to address the drug misuse and diversion problems plaguing this country.

An intervention should be based on self-efficacy beliefs of nurse APs as demonstrated in the survey. The intervention should focus on providing proven strategies. Evidence-based interventions that have proven to be effective include: random drug screening (Fitzsimmons et al., 2018), improved technology and use of automated dispensing cabinets (Brenn et al., 2015), and enhanced continuing education (Luck & Hedrick, 2004). It seems plausible that those individuals who report drug diversion would be supported, helping providers know and feel comfortable reporting drug diversion. Working with facilities to develop policies and plans to address diversion without adverse consequences to the person reporting, a support program for the person diverting medications, and improved education focused on facility-specific policies and procedures should be considered to combat this leading occupational health hazard.

In addition, the important and historic work of Bandura has implications for an intervention. According to Bandura’s (1995), self-efficacy in changing societies, efficacy beliefs can be improved. Based on Bandura’s work, an effective diversion prevention campaign should include communication that will improve efficacy beliefs. Diversion prevention recommendations might include: performance accomplishment, persuasive communication, affective arousal, and vicarious reinforcement. Performance accomplishment can be addressed with open transparency and discussion, setting goals and keeping track of where we are, and where we want to be. Persuasive communication might include reassurance of an individual’s or institution’s ability to actively effect change. Diversion should be a “never happen” event throughout the institution and one’s practice. In essence, providers holding other providers within the department accountable for each other and their success will persuade others and lead them away from drug diversion. Affective arousal is an area where efficacy can be enhanced through positive affect associated with success. One would address what we do well and build upon that to create momentum to diminish misuse and abuse. Vicarious reinforcement is learning through observation and expanding this knowledge and actions to other health care providers. Anesthesia providers commit to, and demonstrate, never having a diversion incident. It is time for APs to own this and pass the knowledge on to others.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: One of the authors received tuition (Ades) and salary (Hammond) funding through grant number T42OH008436 from Deep South ERC. Otherwise, the Deep South ERC had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and decision to publish this project report.

ORCID iDs

Joshua Ades https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6749-5157 Stephanie Hammond https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5400-7169

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in changing societies (pp. 1–45). Cambridge University Press.

Bell, D. M., McDonough, J. P., Ellison, J. S., & Fitzhugh, E. C. (1999). Controlled drug misuse by certified registered nurse anesthetists. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists Journal, 67(2), 133–140.

Berge, K. H., Dillon, K. R., Sikkink, K. M., Taylor, T. K., & Lanier, W. L. (2012). Diversion of drugs within health care facilities, a multiple victim crime: Patterns of diversion, scope, consequences, detection, and prevention. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87(7), 674–682. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.03.013

Bozimowski, G., Groh, C., Rouen, P., & Dosch, M. (2014). The prevalence and patterns of substance abuse among nurse anesthesia students. AANA Journal, 82(4), 277–283.

Brenn, B. R., Kim, M. A., & Hilmas, E. (2015). Development of a computerized monitoring program to identify narcotic diversion in a pediatric anesthesia practice. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 72(16), 1365–1372. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp140691

Bryson, E. O., & Silverstein, J. H. (2008). Addiction and substance abuse in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology, 109(5), 905–917. https://doi. org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181895bc1

DeFord, S., Bonom, J., & Durbin, T. (2019). A review of literature on substance abuse among anaesthesia providers. Journal of Research in Nursing: JRN, 24(8), 587–600. https://doi. org/10.1177/1744987119827353

Epstein, R. H., Gratch, D. M., & Grunwald, Z. (2007). Development of a scheduled drug diversion surveillance system based on an analysis of atypical drug transactions. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 105(4), 1053–1060. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.00000281797.00935.08

Fitzsimmons, M. G., Baker, K., Malhotra, R., Gottlieb, A., Lowenstein, E., & Zapol, W. (2018). Reducing the incidence of substance abuse disorders in anesthesiology residents. Anesthesiology, 129(4), 821–828. https:// doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002348

Lien, C. A. (2012, July). A need to establish programs to detect and prevent drug diversion [Editorial]. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 87(7), 607–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.05.004

Luck, S., & Hedrick, J. (2004). The alarming trend of substance abuse in anesthesia providers. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, 19(5), 308–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2004.06.002

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018, August 9). Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdosedeath-rates

Nursing Theories. (2012). A companion to nursing theories and models. Health Belief Model, http://currentnursing.com/nursing_theory/health_ belief_model.html

Paek, H. (2014). Risk perceptions. In T. L. Thompson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of health communication (Vol. 1, pp. 1190–1191). SAGE. https://doi. org/10.4135/9781483346427.n467

Pelt, M. V., Meyer, T., Garcia, R., Thomas, B. J., & Litman, R. S. (2019). Drug diversion in the anesthesia profession. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 128(1), e2–e4. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003878

Real, K. (2008). Information seeking and workplace safety: A field application of the risk perception attitude framework. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 36(3), 339–359. https://doi. org/10.1080/00909880802101763

Rimal, R. N. (2001). Perceived risk and self-efficacy as motivators: Understanding individuals’ long-term use of health information. Journal of Communication, 51(4), 633–654. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02900.x

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change. Human Communication Research, 29(3), 370–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2003.tb00844.x

Samuelson, S. T., & Bryson, E. O. (2017). The impaired anesthesiologist: What you should know about substance abuse. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia, 64(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-016- 0780-1

Sederer, L. (2015, June 1). A blind eye to addiction. US News and World Report. https://www.usnews.com/opinion/blogs/policydose/2015/06/01/america-is-neglecting-its-addiction-problem

Tetzlaff, J., Collins, G. B., Brown, D. L., Pollock, G., & Popa, D. (2010). A strategy to prevent substance abuse in an academic anesthesiology department. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 22(2), 143–150. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.clinane.2008.12.030

Upton, D., & Upton, P. (2006). Development of an evidence-based practice questionnaire for nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 53(4), 454–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03739.x